The History of Bells: Sound, Culture, and Engineering

/ 6 min read

Table of Contents

The Resonant Journey: A Deep Dive into the History of Bells

From the delicate chime of a tiny ornament to the profound rumble of a towering cathedral bell, these resonant objects have captivated humanity for millennia. Bells are more than just instruments; they are vessels of history, culture, and remarkable engineering prowess, shaping our societies in ways we often take for granted. Let’s embark on a journey through time to uncover the multifaceted story of the bell.

Early Origins: The Dawn of Sound

The earliest predecessors of bells were likely simple percussive objects made from natural materials. Hollow gourds, shells, or pieces of wood struck together would have served basic communication or ritualistic purposes in prehistoric societies. The transition to more durable, resonant materials marked a significant step. Archaeological evidence suggests that early metal bells, possibly made of copper or bronze, emerged independently in various parts of the world, particularly in ancient China and the Near East, over 4,000 years ago. These initial forms were often quite small, used as adornments, musical instruments, or warning devices.

Bells in Ancient Civilizations: Symbolism and Function

As metallurgical techniques advanced, so did the complexity and significance of bells.

-

Ancient China: China holds one of the longest and most sophisticated histories of bell-making. Dating back to the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), highly ornate bronze bells, known as zhong and nao, were cast with incredible precision. These were not simply percussive; they were often sets of bells tuned to specific musical scales, forming complex orchestras used in elaborate court rituals, religious ceremonies, and ancestor worship. Some of these ancient bells can still produce beautiful, complex tones today, a testament to their advanced engineering.

-

Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia: While less prominent than in China, small bells of various metals were used in these regions for ritualistic purposes, to ward off evil spirits, or as decorative elements on clothing and animal harnesses.

-

Classical Greece and Rome: The Greeks used small bells (krotala) in religious rites, particularly those associated with Dionysus, and as signals. The Romans adopted bells more broadly, creating tintinnabula – small bells often hung in doorways or gardens to announce visitors or ward off bad luck. They also used larger bells for public announcements, signaling the opening of markets, or calling people to baths.

The Medieval Era and Beyond: The Rise of Church Bells

The early Christian church initially viewed bells with suspicion due to their pagan associations. However, by the 6th century CE, bells began to be adopted in monasteries as a way to call monks to prayer. This marked a pivotal moment, as bells quickly became indispensable to Christian worship and community life across Europe.

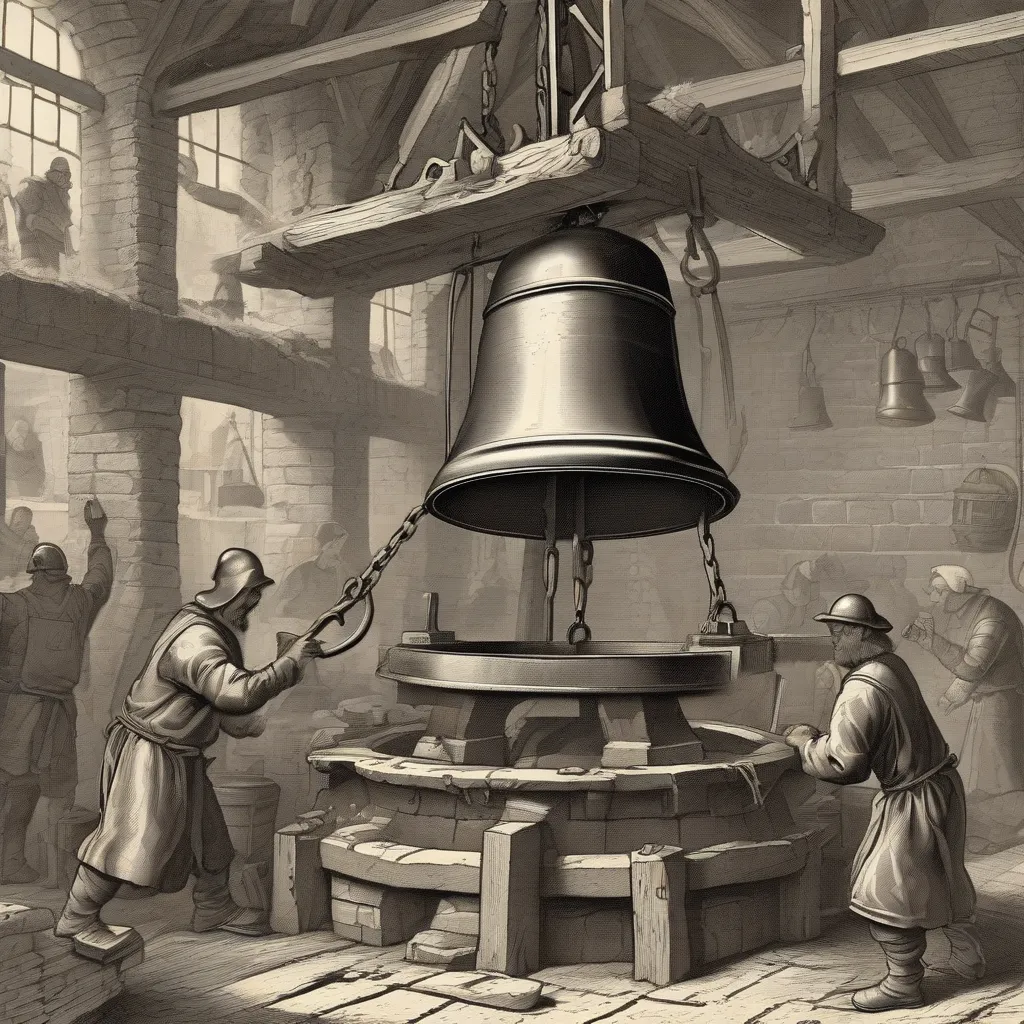

The need for larger, louder bells to reach wider congregations spurred significant advancements in metallurgy and casting techniques. Medieval bell founders became highly skilled artisans, often traveling from town to town to cast bells directly on-site due to their immense size and weight. These bells, typically made of “bell metal” – an alloy of roughly 80% copper and 20% tin – produced a rich, resonant tone far superior to earlier forms.

Beyond religious functions, church bells became the heartbeat of medieval towns:

- Timekeeping: They marked the hours, guiding daily life before widespread mechanical clocks.

- Alarms: Tolling in specific patterns to warn of fires, invasions, or other dangers.

- Celebrations: Pealing joyfully for weddings, coronations, and victories.

- Mourning: Slow, solemn tolls for funerals.

This era saw the development of bell towers (campaniles) that became iconic architectural features, often the tallest structures in a town, symbolizing its wealth and piety.

Engineering Marvels: From Bronze to Carillons

The science of bell-making continued to evolve dramatically, particularly from the Renaissance onward.

-

Metallurgy and Acoustics: The precise proportions of copper and tin in bell metal were critical. Copper provided ductility and strength, while tin increased hardness and improved the bell’s resonant qualities. Founders learned to control the harmonic overtones produced by a bell by meticulously shaping its profile. A well-tuned bell produces not just a fundamental note, but a rich chord of harmonious partials (hum note, fundamental, tierce, quint, nominal), which gives it its characteristic depth and warmth.

-

Gigantic Bells: The ambition to cast ever-larger bells pushed engineering boundaries. The most famous example is Russia’s Tsar Bell, cast in the 1730s. Weighing an astonishing 201 tons (402,000 pounds) and standing over 20 feet tall, it remains the largest bell ever cast, though it unfortunately cracked during a fire before ever being rung. In contrast, Big Ben, the iconic bell in London’s Elizabeth Tower, weighs a robust 13.5 tons and has been faithfully marking time since 1859.

-

Carillons: Originating in the Low Countries (modern-day Belgium and the Netherlands) in the 16th century, the carillon is a musical instrument consisting of at least 23 cast bronze bells, precisely tuned and played from a keyboard. The development of sophisticated mechanisms to connect the keyboard to the clappers allowed for complex melodies and harmonies. Today, there are around 600 carillons worldwide, predominantly in Europe and North America, serving as magnificent public musical instruments.

Bells Across Cultures: Diverse Roles and Meanings

While European church bells are widely recognized, bells have played equally vital and varied roles in other cultures:

-

Buddhist Temple Bells (Japan, Korea, China): These massive, often elaborately decorated bells are struck externally with a wooden beam. Their deep, lingering tones are believed to purify the air, calm the mind, and guide souls. The precise moment and rhythm of their ringing are deeply significant in ceremonies.

-

Hindu and Jain Temple Bells (India): Smaller, hand-held bells are rung by devotees to announce their presence to the deity and to invoke auspiciousness during puja (worship). Larger bells are also found at temple entrances.

-

Cowbells and Animal Bells: From the Swiss Alps to African savannas, simple bells have been used for millennia to keep track of livestock, their distinct sounds helping herders locate their animals.

-

Musical Instruments: Beyond carillons, bells feature in numerous musical traditions, from handbells played by choirs to the vibrant bell sections in orchestras and marching bands.

The Modern Bell: Tradition Meets Innovation

In the contemporary world, the traditional bell continues to resonate. Existing bells are carefully preserved and restored, often requiring specialist knowledge and techniques that have been passed down through generations. New bells are still cast for churches, universities, and public institutions, employing both traditional methods and modern acoustic analysis to achieve perfect tones.

While digital technology allows for synthesized bell sounds, the unique acoustic complexity and physical presence of a true bronze bell remain unparalleled. They continue to serve as powerful cultural markers, summoning communities, commemorating events, and providing a sonic link to our shared past. The bell, in all its forms, remains a profound testament to human ingenuity and our enduring fascination with sound.